Federal judge who called Trump a 'criminal' and faced misconduct finding dies at 78

Robert Pratt, the federal judge who called President Donald Trump "a criminal" and faced an official misconduct finding for his remarks, died Wednesday of a heart attack, the New York Times reported. He was 78. His son Michael confirmed he collapsed in a gym in Clive, Iowa.

Pratt served 26 years on the federal bench in Iowa, a tenure marked by rulings that struck down abortion restrictions and a prison faith program—and by public comments about Trump that his own appeals court characterized as misconduct.

The comments came in 2020, shortly after Trump issued pardons for campaign aides John Tate and Jesse Benton, along with Paul Manafort and four Blackwater security guards. Pratt did not hold back when an Associated Press reporter called.

The Remarks That Drew Rebuke

Pratt told the AP:

"It's not surprising that a criminal like Trump pardons other criminals."

He continued:

"But apparently to get a pardon, one has to be either a Republican, a convicted child murderer or a turkey."

The comments drew immediate attention. Fix the Court, a judicial ethics watchdog, brought them to the attention of Lavenski Smith, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. Smith characterized the remarks as "cognizable misconduct."

In an April 16, 2021 letter to Smith, Pratt acknowledged "the wrongfulness of the comments." He wrote:

"I regret the embarrassment they have caused to my court and the judiciary in general."

The episode crystallized a tension that runs through the federal judiciary: judges who hold lifetime appointments and wield enormous power, yet sometimes forget that their authority rests on the perception of impartiality.

A Clinton Appointee's Path to the Bench

Pratt was born May 3, 1947, in Emmetsburg, Iowa. He earned his law degree from Creighton University in 1972 and spent 22 years in private practice before ascending to the federal bench.

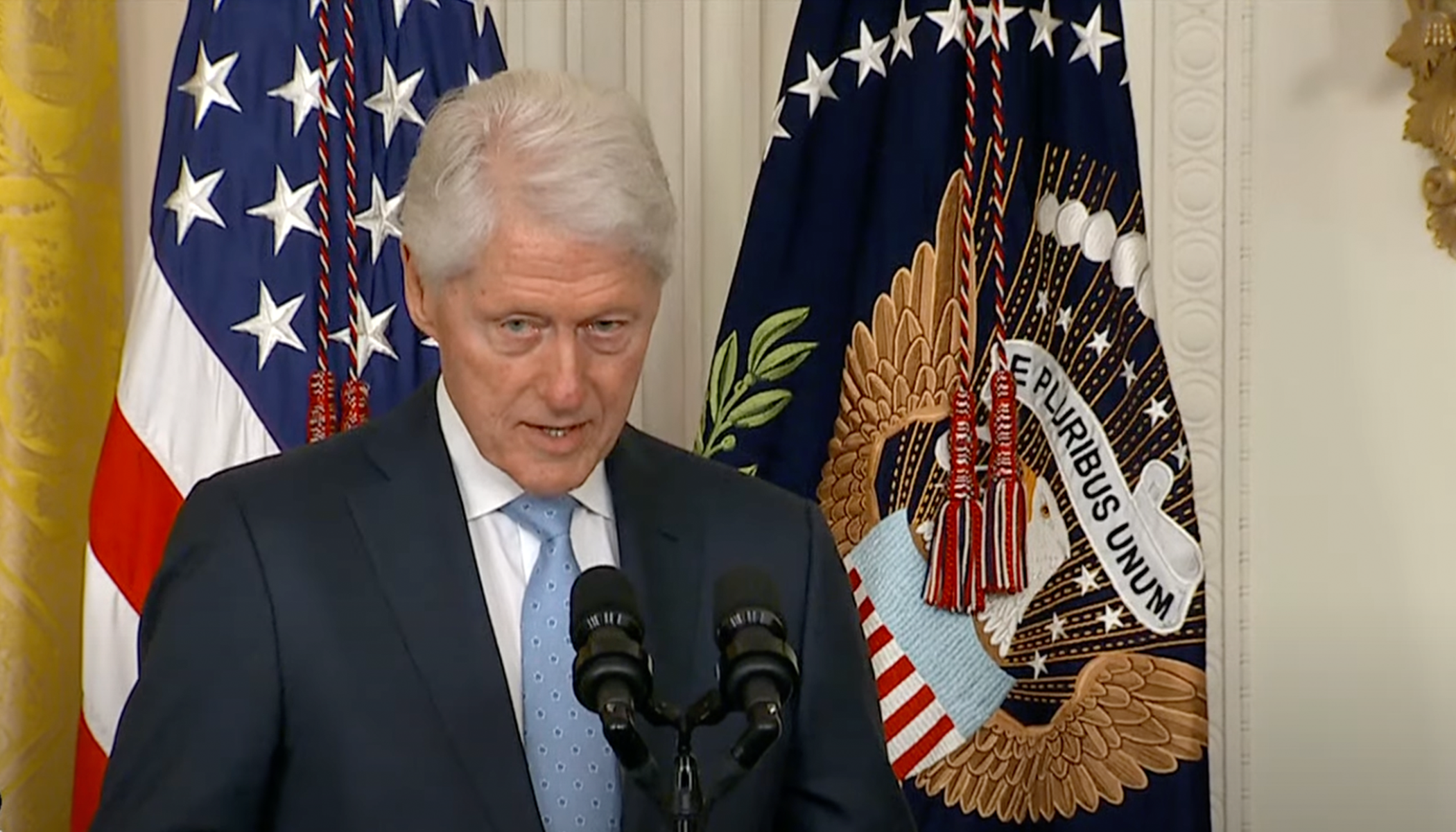

His path to the judgeship ran through Democratic politics. At the Polk County Legal Aid Society in Des Moines, he met Tom Harkin—then a young lawyer, later a U.S. senator from Iowa. When a seat opened in 1997, Harkin recommended Pratt. President Bill Clinton nominated him.

Pratt reflected on his legal career to The Des Moines Register that year:

"If my legal practice stood for anything, it was getting access to the system for people who otherwise would not have it."

That philosophy would guide—and sometimes define—his judicial approach.

Rulings That Shaped Iowa

Pratt's most consequential decisions aligned with liberal legal priorities. In 1998, he struck down a year-old state law banning late-term abortions—specifically, the second-trimester dilation and extraction procedure. The Eighth Circuit upheld his ruling.

In 2006, he ruled that a state-funded prison rehabilitation program in Newton, Iowa violated the First Amendment. The program promoted evangelical Christianity, which Pratt deemed "pervasively sectarian." The appeals court agreed with his conclusion but set aside his order requiring more than $1 million in repayment.

His 2005 sentencing of convicted ecstasy dealer Brian Gall tested the boundaries of judicial discretion. Federal guidelines called for up to 37 months in prison. Pratt, convinced Gall had rehabilitated himself, imposed three years of probation instead. The appeals court reversed him. The Supreme Court reinstated his decision in 2007.

The Sorenson Case

Pratt's connection to the Trump pardon controversy ran through Kent Sorenson, a former Iowa state senator who pleaded guilty to two crimes including violating federal election law.

Sorenson had endorsed Congresswoman Michele Bachmann for the 2012 Iowa Republican presidential caucuses—then revoked that endorsement days before the vote in favor of Representative Ron Paul. The switch wasn't ideological. Paul campaign aides John Tate and Jesse Benton had arranged $73,000 in hidden payments to secure it.

Tate and Benton were convicted in 2016. A year later, Sorenson came before Pratt for sentencing. Prosecutors recommended probation. Pratt rejected that recommendation and sentenced Sorenson to 15 months in prison, calling the scheme "the definition of political corruption."

When Trump pardoned Tate and Benton shortly before Christmas 2020, Pratt's public comments followed.

The Naturalization Tradition

Not all of Pratt's legacy was controversy. In 2009, he began an annual tradition of presiding over naturalization ceremonies around July 4 at Principal Park in Des Moines.

In 2020, unable to attend due to the pandemic, he sent written remarks that captured his view of American identity:

"You may hear voices in this land say that there is only one true American set of values. Do not believe it. As an American, you may openly hold beliefs and values greatly different from those of others — even if those of others are shared by many and yours are shared by few."

The sentiment reflected a pluralism that Pratt valued. Whether it sat comfortably alongside his willingness to publicly condemn a sitting president as a criminal is another question.

A Judge and His Limits

Pratt retired in 2023. He is survived by his wife, Rose Mary Vito Pratt; his children Michael, Kathleen Loughney, and Christopher Pratt; stepdaughter Susie Scanlon; siblings Ruth Neppl, Mary Jane McWilliams, and James Pratt; and seven grandchildren.

His death closes a chapter on a judge who saw himself as a champion of access and fairness—but who, in one memorable moment, revealed the partisan assumptions that can lurk beneath the robe. The Eighth Circuit's misconduct finding stands as part of his record, alongside the rulings and the naturalization ceremonies.

Federal judges serve for life precisely because they are supposed to stand apart from politics. Pratt's career showed how difficult that separation can be—and what happens when a judge forgets it entirely.

He called a sitting president a criminal from his position of public trust. His own court called that misconduct. Both facts belong to history now.