Obama-appointed judge orders release of four criminal illegal immigrants from ICE custody at Angola

A federal judge in Louisiana ordered four illegal immigrants — including three with attempted murder or manslaughter convictions and one convicted of sexually exploiting a minor — released from ICE detention, drawing a fierce rebuke from the Department of Homeland Security.

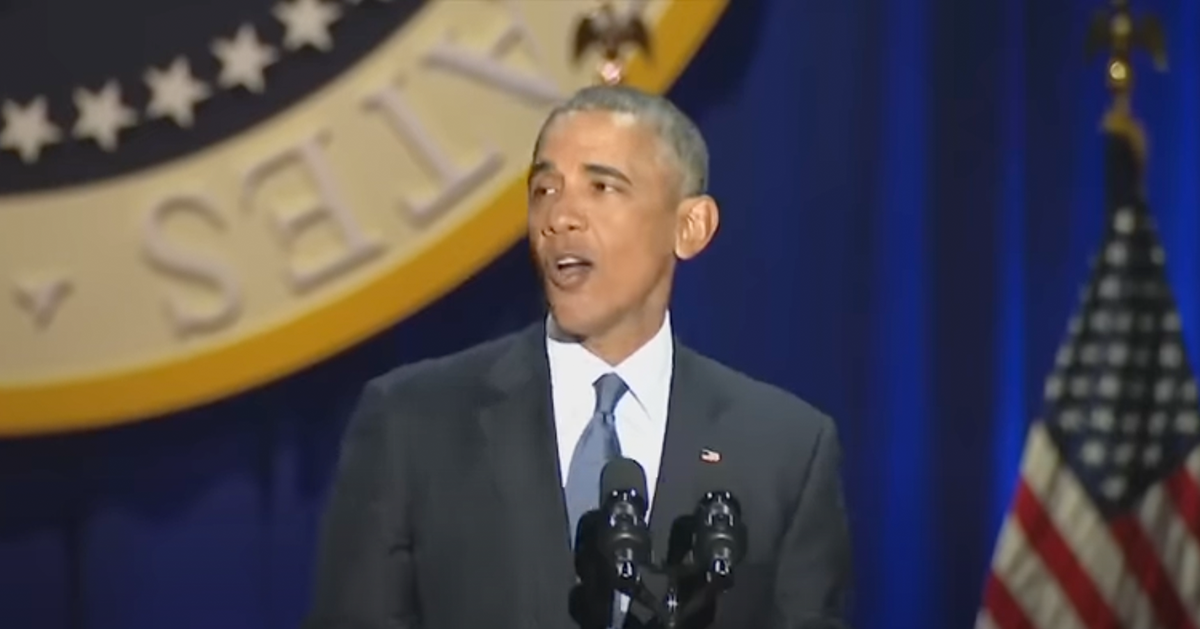

Judge John deGravelles, an Obama appointee on the Middle District Court of Louisiana, granted the release, finding that the men's continued detention was unlawful. DHS fired back on Wednesday, calling the decision "inexcusably reckless" and labeling deGravelles an "activist judge."

The four men were among the first detainees held at Camp 57 — the so-called "Louisiana Lockup" — a facility at Angola Prison that DHS began renting from the state of Louisiana in September 2025 to expand ICE detention capacity.

Who walked out

The released individuals are not petty offenders caught up in a paperwork dispute. Their criminal records speak plainly:

- Ibrahim Ali Mohammed, an Ethiopian national, was previously convicted of sexual exploitation of a minor. A final order of removal was issued in September 2024.

- Luis Gaston-Sanchez, a Cuban national, has convictions for attempted murder, assault, resisting an officer, concealing stolen property, and two counts of robbery. His deportation order dates back to September 24, 2001. He served 19 years and was released on good behavior in 2023.

- Ricardo Blanco Chomat, a Cuban national, was convicted of attempted murder, kidnapping, aggravated assault with a firearm, burglary, robbery, larceny, and selling cocaine. His removal order was issued in March 2002.

- Francisco Rodriguez-Romero, a 72-year-old Cuban national, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter in 1990 and released in 1995. His final order of removal has been in place since May 1995 — nearly 31 years.

Three of the four are Cuban nationals over 60. All four were re-detained in the summer of 2025 — three after showing up for routine ICE check-ins, and one after agents came to his home.

The judge's reasoning — and the law he's leaning on

According to the New York Post, DeGravelles based his ruling on the 2001 Supreme Court decision in Zadvydas v. Davis, which holds that illegal immigrants cannot be held in detention for longer than six months unless there is a reasonable chance they are about to be deported. The judge wrote that detention beyond that threshold is "constitutionally suspect" and concluded that for these four men, "their deportation is not reasonably foreseeable."

He ordered their immediate release within three hours.

In his decision, deGravelles addressed the government's argument that each of the men was a dangerous criminal. He acknowledged their convictions but wrote that their criminal histories were "irrelevant to the analysis" — reasoning that each man had already served his sentence and that ICE itself had previously determined each one should be released into civilian life.

That reasoning carries a certain bureaucratic logic. It also requires you to ignore what these men were convicted of doing. A judge telling the public that attempted murder convictions and child sex offenses are "irrelevant" — because the sentence was already served — is the kind of legal reasoning that makes ordinary Americans distrust the judiciary. The law may permit it. Common sense recoils from it.

DHS doesn't mince words

DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin made the department's position unambiguous. On Wednesday, she issued a statement that went well beyond standard agency boilerplate:

Judge John deGravelles, appointed by Barack Obama, released FOUR violent criminals back onto American communities, and unfortunately, the ramifications will only be the continued rape, murder, assault, and robbery of more American victims.

Releasing these monsters is inexcusably reckless.

McLaughlin also framed the broader enforcement posture clearly:

We are applying the law as written. If an immigration judge finds an illegal alien has no right to be in this country, we are going to remove them. Period.

DHS added that despite a "historic number of rulings from activist judges," the department is "working rapidly and overtime to remove these aliens from detentions centers to their final destination — home."

The deportation problem no one wants to solve

Here's where the story gets structurally frustrating. Three of these men are Cuban nationals. Cuba has historically refused to accept deportees from the United States — a diplomatic standoff that has persisted across administrations of both parties. DeGravelles noted in his ruling that Mexico has not agreed to accept the Cuban men either, possibly because all three are over 60 and one has two age-related degenerative diseases.

So the legal framework works like this: the U.S. issues a removal order, the home country refuses to take the person back, detention stretches past six months, and a federal judge orders release because deportation isn't "reasonably foreseeable." The illegal immigrant — conviction record and all — walks free. Not because the system worked, but because it was designed to collapse at exactly this point.

The Zadvydas decision created a perverse incentive. If your country of origin refuses to cooperate, your detention has an expiration date. The worse your home government behaves diplomatically, the better your chances of release into American communities. That's not justice. It's a loophole dressed in constitutional language.

What DHS characterized vs. what the records show

It's worth noting a discrepancy in how DHS described these men's records. The department's press release characterized all three Cuban nationals as having been convicted of "murder." The actual convictions, as reported by Verite News, tell a slightly different story: Gaston-Sanchez and Blanco Chomat were convicted of attempted murder, not completed homicide, and Rodriguez-Romero was convicted of involuntary manslaughter.

These are not trivial distinctions in a legal system built on precision. Attempted murder and involuntary manslaughter are serious crimes — no one is minimizing that. But when a federal agency inflates charges in a press release, it hands ammunition to the other side and undermines the credibility of an argument that should be able to stand on its own merits. The actual convictions are damning enough without embellishment.

The bigger pattern

This case fits neatly into a dynamic that has played out repeatedly since the current administration began expanding immigration enforcement. Federal judges — many appointed by Democratic presidents — have issued rulings that functionally obstruct removal efforts. The administration pushes forward. The judiciary pushes back. And the people caught in the middle are American communities that have no say in whether a man convicted of attempted murder or child sexual exploitation lives in their neighborhood.

The immigrant rights attorneys who filed the habeas petition — reportedly the National Immigration Project and Rights Behind Bars — did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did the judge's court. The silence is telling, if unsurprising. It's much easier to secure a release order than to defend it publicly.

Meanwhile, the men whose deportation orders span decades — one dating back to 1995 — are free again. Their removal orders remain on the books. The countries that should take them back still won't. And the legal architecture that was supposed to balance liberty against public safety just tipped the scales toward men who've already demonstrated what they do with freedom.

Four men walked out of Angola on a Friday afternoon. The judge gave ICE three hours to open the doors.